Net neutrality, bots, and the FCC: a retrospective

December 14th, 2017: The FCC voted. There are 23 million comments on the docket. How has our conversation about net neutrality shifted? What lessons does that hold for our future? Here are some collected thoughts on three things: how we’ve talked about net neutrality, how we’ve misunderstood “bots”, and how the comment process may need to evolve.

(For those just tuning in, here’s a quick primer on what happened.)

Part 1: How We Talk to the FCC

1. What does net neutrality mean to us?

It goes without saying that the FCC’s actions have ignited a firestorm. Our discussion of net neutrality has far surpassed its original technical and legal context. Those talking heads on CNN weren’t arguing over the finer points of the Communications Act of 1934.

Instead, net neutrality has become a byword which means many things to many different people. In no particular order, it has become a stand-in for:

- our abstract idea of the “Open Internet”

- consumer dissatisfaction with telecom monopolies

- job creation and infrastructure investment

- support for entrepreneurship and American competitiveness

- influence of money in politics

- related battles over privacy, surveillance, and online freedom

- fake news and “bots”

- worry about Russian interference in United States affairs

- pushes for government transparency

- how the government and public interact

- not least of all, an ugly proxy battle with a Trump Administration appointee (specifically, Ajit Pai)

The list goes on. We have to recognize that there are dozens of separate discussions occurring. First, we have the technical and legal issues surrounding Title II reclassification. Second (through tenth, or twentieth) we have these adjacent conversations about policy, economics, and politics. At the bottom of the stack, there remains the larger issue of how we engage with our policy process — and how the Internet is shaping that.

I believe that last one is a question that we’ll be returning to again and again.

2. How should we view the FCC’s comment process?

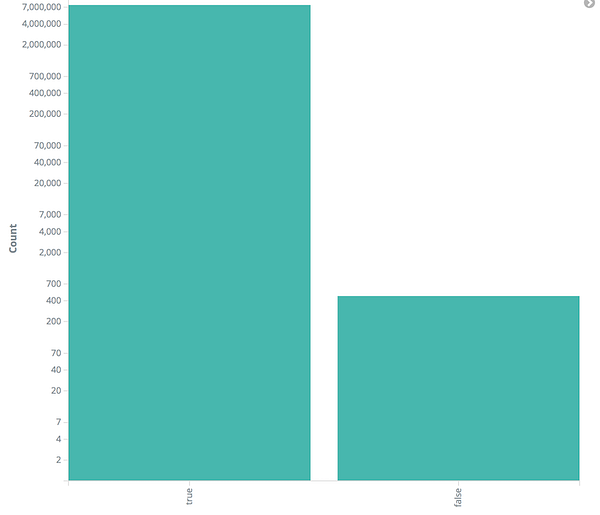

According Jeff Kao, “More than a Million Pro-Repeal Net Neutrality Comments were Likely Faked.” Or, from the Washington Post: “FCC net neutrality process ‘corrupted’ by fake comments and vanishing consumer complaints, officials say.”

Is this a problem? Let’s examine why someone would think it is — or isn’t.

Viewpoint A: Public comment is working fine.

“As I said previously, the raw number is not as important as the substantive comments that are in the record,” Pai said. “We want to weigh all comments and make sure that we take a full view of the record, and again make the appropriate judgment based on those facts and the law as it applies.”

Why does the public comment system exist in the first place? The FCC is an expert agency and uses the public comment process to solicit alternative viewpoints and analyses it may not know about or have considered. Opportunity to comment during a Federal agency’s rulemaking process is a broad requirement of the 1946 Administrative Procedure Act.

The FCC makes a lot of rules, so most dockets are about relatively niche telecom issues. For example, take 17–239 “Inquiry Concerning 911 Access, Routing, and Location in Enterprise Communications Systems”: there are under 30 filed comments, all of which are from industry, government, or academia. This is the use case that the FCC built its comment process for. This is also the reason why Chairman Pai was able to factually state that the “raw number” of comments is not important: the FCC isn’t under any obligation to equally weigh the comments it receives.

In other words, the FCC’s comment system was not built to be a public opinion poll. It was built to solicit very specific types of feedback and analysis. It seems to be doing a fine job of that.

Viewpoint B: But it is a problem!

“Before my fellow FCC members vote to dismantle net neutrality, they need to get out from behind their desks and computers and speak to the public directly. The FCC needs to hold hearings around the country to get a better sense of how the public feels about the proposal.” — FCC Commissioner Rosenworcel

While the comment process may work in a narrow scope, we’ve seen a lot of issues manifest themselves on the net neutrality docket. We need to think about how the comment system can evolve to serve the public in new ways.

First, we have a gap in perception between how the FCC thinks the comment system should work and how the public thinks the comment system actually works. The FCC thinks that the status quo “expert alternative viewpoint” model is sustainable. However, the public thinks the process should be more like an opinion poll and reflect popular sentiment. Therefore, they feel like they’re being denied a voice in the process and that the FCC is turning a blind eye.

Second, we need to ensure that the FCC is not ignoring legitimate requests to correct the record or obtain information. The Commission’s reticence in dealing with the New York Attorney General’s fraud investigation and alleged reliance on technical inaccuracies in its regulatory argument are worrying. A flawed rulemaking process leads to flawed rules: this is something I hope we can agree on, regardless of ideology.

Finally — of course — we need to make sure that individuals’ identities aren’t being borrowed (to put it diplomatically) and attached to statements that aren’t their own. The fact that individuals or groups have done this throughout the comment process indicates they think sufficient commenting firepower will be sufficient to sway the public or media discourse about the subject. Whether or not that effect actually holds is up for debate. However, it does indicate we need to examine the incentives (and legality) around this kind of behavior.

3. So, has the comment process been “corrupted”?

The argument for “no”: The core mechanics of the FCC’s comment system have not been broken. If we agree that the FCC’s existing processes are sufficient for the specific purpose of providing alternative viewpoints into the rulemaking process, there has been no corruption of that process.

The argument for “yes”: It’s not corrupted, but it’s certainly fraying at the edges. Even if the process is working for the vast majority of issues, that’s not sufficient. We have a disconnect between how the public and FCC view the process. We also have bad incentives at play: It’s hard to claim that a process that allows for criminal impersonation is totally sound. Finally, we have institutional issues at play with the FCC if it does turn out that those technical inaccuracies are core to the logic of the current rule-making.

As issues of telecom and Internet policy loom larger in the public consciousness — and as they unavoidably become politicized — we need to find better outlets for engagement and opinion to filter into the FCC’s policy processes.

Part 2: Bots — A Quick Aside

The use of bots during the comment period has gotten a lot of play in the media. Are bots bad? And how do they affect how we think about the future of public comment?

1. What is a bot?

First, though, we need to clarify what exactly a “bot” is in this case and why it’s different from other bots you might be familiar with. Here, I’m going to define a bot as a “program designed to automatically post comments in bulk to the FCC’s systems.” Note there is no value judgment attached to this definition: it’s purely technical. Why?

Generally when we talk about bots, we think about automated actors playing in a space that was created for humans to interact in. Think about bots in online gaming or “fake news” bots posting on Facebook. In both cases, there’s the assumption that the (gamer / poster) is a human and that the person using the bot will gain an unwanted advantage in (winning / spreading information). Here, we agree bots are bad because you’re playing a human system with a computer that presents itself like other humans.

This is not the case with the FCC’s Electronic Comment Filing System (ECFS). The ECFS was designed from the outset with an API — an interface that lets programs automatically interface with the ECFS. In fact, the FCC conveniently provides documentation for developers to… wait for it… automatically file comments in bulk.

2. Are bots bad?

The FCC’s API has very few limitations and a very light amount of internal rate limiting. Because of this, we’re working in a different space than Facebook or Counter-Strike where the platform was designed for humans first. It’s often said that a system’s design shapes the behavior of its users. In this case, FCC’s decision to tilt towards frictionless comment has enabled a whole host of unforeseen, automated uses of the system.

Not all bots are bad.

It’s no surprise that there are bots filing comments because that’s what the FCC wanted. In fact, it’s hard to argue that the open design of the ECFS hasn’t been good for advocates on both sides of the debate. Interest groups have created numerous websites that automatically file comments with the FCC creating an unprecedented level of engagement. You wouldn’t be seeing the explosion of “make your voice heard!” campaigns and sites without the underlying ECFS infrastructure.

Of course, the ECFS’ open design has also allowed researchers and other interested parties to download, analyze, and understand the comment process at a very deep level. This is a good thing.

…but they can be, depending on intent.

Remember the mention of the New York Attorney General’s Office and their investigation into fake comments? That came about because several researchers discovered a disturbing pattern: many individuals’ names and identities were being attached to comments that they did not make. This is undeniably a Bad Thing. Individuals’ names should not be on the public record attached to opinions that they did not state.

It’s important to remember: there is no technical difference between a “good bot” and a “bad bot” here. The same code that a developer uses to automatically file comments from an EFF or AT&T campaign could also be used to file fake comments with fake identities attached. It’s just a matter of switching out the database or spreadsheet.

Part 3: What’s Next?

The frictionless comment infrastructure that the FCC built has enabled bad actors to stuff that infrastructure with fake identities and fake documents. That’s not a sustainable path for public comment; I don’t believe so, the New York Attorney General doesn’t think so, and neither do dozens of Senators. At the same time, we don’t want to throw away the civic benefits of a platform that allows for open engagement.

We need to think about a core question: How do we disincentivize these bad-faith acts on the comment system while still maintaining an open-enough infrastructure to enable the good?

Striking the right incentive balance is a design and policy question that the FCC — and likeminded agencies — need to strongly consider as they create systems for public engagement. Should known bad comments be discarded, de-ranked, or ignored? Should there be a burden of proof for claimed identities attached to comments? How about not-good-but-not-bad grey areas, like the 7.5 million identical comments that used throwaway emails?

We may want to augment the existing comment process by equipping the FCC with the tools and expertise it needs to characterize the massive amount of comments it has received. This works towards the current “deluge of data” problem and embeds extra, necessary capabilities within the FCC’s institutional structure. It would also equip the FCC with the tools it needs to begin addressing the issue of stolen identities mentioned above.

On the other hand, augmentation presents a short-term solution to a long-term problem: we should be thinking more holistically about interaction with agencies like the FCC. Expert commentary and analysis is invaluable during the rulemaking process, we should make the effort to understand how the public can and should provide input into the process. Whether this is through existing mechanisms like public hearings and listening tours or through a more elaborate process, tweaks to the process deserve some thought.

We also need to think about what lessons we might draw from the net neutrality comment process. A recent Wall Street Journal investigation found a large number of comments on a Department of Labor rulemaking were attributed to individuals whose identities were “borrowed” for the comment. These Labor proceedings aren’t on the scale of the net neutrality ones and contain thousands, instead of millions, of comments. However, the article lets us revisit the idea of incentives and system design. Someone was sufficiently motivated to file fake comments and the frictionless nature of the system’s design allowed them to with a minimum amount of fuss.

What about the comment system’s technical design allowed this to happen? What incentives were at play? Why did the commenter think that “stuffing the ballot box” with comments would help their position, either in the regulatory world or in the broader public discourse? As with the ECFS, these questions should be thought and investigated.

To wrap up, though: whatever the future of public comment holds, all of this drama surrounding the net neutrality comment process is quite telling. Whether it’s the FCC, Department of Labor, or something else, we’re not going to be going back to a world where these niche policy debates will be conducted on purely technical or legal terms. We — both as individuals and as our government — need to be prepared for that new reality.